Cynthia Yee, Yee Li Hing, 余麗馨

March 2021

1958 Boston Chinatown

I had to go to the Kwong Kow Chinese School after American School every afternoon for three hours, and every Saturday morning, too. Three days earlier, I’d quit. I hadn’t told anybody, not my Dad, not my teachers, and certainly not MaMa. I’d just stopped showing up. I had not planned where I would go or what I would do, so I wandered. Empty streets. Dark recessed doorways. Friendless stoops. Abandoned gas stations. I stopped in the middle of the vacant lot at the corner of Hudson and Oak. In the waning October light, a slight chill in the air slipped through my brown corduroy pants. I kicked one pebble, then another. I kicked pebbles in circles, spiraling outward. A building had once stood on this lot, now nice empty space, good for killing time until Chinese School let out.

At home, past the olives and nuts store, past the alley where a Syrian girl once cornered me, and three row houses down, MaMa had enough to cry about. Tears already fell onto the fabric slipping through her fingers as she sewed. She’d had to leave three daughters in China, one dead in her grave, but she didn’t talk about that one. Her precious second daughter was now hauling bricks to build the New China, singing revolutionary songs, praising her new god, the Father of her country, the Chairman. Talking about the bricks, MaMa’s voice rose, agitated. Aunty Cheong Sim said, “Carrying bricks will be good for that lazy girl of yours.” MaMa’s tears flowed more. The last thing MaMa needed now was a renegade daughter, an American girl, running loose, in an empty city lot in a western land.

I had turned nine a few months earlier. Babies in China often died, so a baby’s birth was celebrated when the baby turned one month, a baby living through the first month, likely to survive and grow, a birth worth celebrating with ceremony. Snipping a lock of the baby’s hair, rolling two boiled eggs on the baby’s head, chanting special blessings, then handing the eggs to the older children to eat, telling them to care for the child, admonishing the baby to obey elder siblings and cousins, then giving the baby a special name to bless and protect him. Red eggs and ginger. Chicken wine soup with cloud ear fungi and day-lilies. Sweet and sour black vinegar soup with pork trotters, sweet potatoes, and eggs. A party to announce a new life. After that, children did not get birthday parties, only grown ups, because they had lived and survived. Children, still growing, had not lived life, so no big celebrations, only a drumstick with family. Nothing to attract jealous gods.

My Dad had given me a ninth birthday party, my only ever birthday party. Not just chicken drumsticks and noodles with family, but with friends, on a Saturday afternoon after Chinese School. Party hats, party napkins, cake, candles, ginger ale and root beer, vanilla, chocolate, or strawberry ice cream to make floats. My Dad had sailed from China to America when he was twelve, had returned to China to marry MaMa when they were eighteen, and left my pregnant MaMa for America after one year. He returned to China once more, then left my again pregnant MaMa and two daughters, to work in America, and fight a war in Europe. He never returned to China again. He had taken on American ways, American movies, American music, and had given an American birthday party for his only American-born child.

Every day, from 2:00 p.m.until 1:00 a.m. my dear old Dad ushered white folks into the Cathay House with a smile, and a cheery, “How are you this evening?” I often sat and watched him in action. After Chinese School on weekday evenings, I passed by the restaurant on Beach Street and sometimes, I went in the front door. But often I got out of Chinese School late, because we had to sign our names on our work in Chinese before leaving, and I always forgot. I was often last out. My Uncle Cheong Sook had named me, Yee Li-Hing 余麗馨 Beautiful Fragrance, 45 strokes total, a signature over five inches long. My friend, Karen, Chin LLiu Ngook 陳秀⽟ Embroidered Jade, watched at the classroom door, laughing, while I plodded down the page. Chin Lliu Ngook 陳秀⽟ had only 22 strokes total, half the number of mine. 4 strokes, three horizontal, one vertical, and a water drop, ⽟ Ngook Jade, and she was done. 20 strokes, horizontals, verticals, strokes curving to the left, and strokes curving to the right, 馨 Hing Fragrance before I could leave. “I hate this name. It’s so long,” I said. While I wrote, Karen giggled, but waited. I finished the last horizontal stroke, closed a square, locking a short horizontal stroke inside.

Aunty Cheong Sim, the best cook in the world, and illiterate in Chinese and English, had said,“Your Hing is the most beautiful name of all.”

“Fragrance is a stupid name. It’s a smell, it floats, and disappears into the air. It’s not strong. What’s so good about that? I like a strong name. How about Fiery Dragon or Fierce Tiger?” I had said.

Uncle Cheong Sook, wrinkling his brow and shaking his head at my suggestion, had chimed in, “Fragrance is strong and beautiful. It’s a good name for you. Fragrance travels everywhere, is welcomed and noticed by everyone, and is hard to hold down.” “It takes too long; it’s too hard to write,” I’d said.

But it was too late. Li Hing 麗馨 Beautiful Fragrance, was what all Chinatown called me.

After my Chinese School friends and I finally got out of school, we walked by the Cathay House to get to Hudson Street. I stopped at the door and said to them, “Come on in.” Dad, my handsome Uncle Ai-Sook, and the waiters smiled at us. As though we were their warmest silk vests in the coldest winter.

“Want some ice cream?” Dad asked.

At these moments, I felt proud. This cheery man in his dark suit and tie, speaking good English, is my Dad.

“Go around to the back,” he said.

We scrambled out the front door, around the corner to Edinboro, a dark alley, and in through the kitchen door. My three friends and I crowded into the kitchen. My Dad, standing there waiting, looked at me, then nodded at the cooks.

“Remember to greet people, Hahm ngin,” Dad reminded me.

The kitchen uncles dressed in white caps, white shirts, white pants, and dusty black shoes. I knew to call them, “Ah Sook,” if they looked younger than my Dad, “Ah Bak,“ if they looked a bit older, and, “Ah Gung,” if they looked ancient, like, ready to tip over. I knew the dishwasher uncle, lugging a tall stack of dirty dishes, had to be “Ah Gung,” for sure. I compared each to my kinda youthful, kinda old, balding Dad. Dad had never introduced me to them, one by one. He left me to judge age compared to him. I liked that he trusted my instincts in this important matter.

“Ah Gung!” “Ah Sook!” “Ah Bak!” I greeted them in my cheeriest voice. Their broad smiles felt like hugs. The three kitchen uncles said, “Fong hok le mo? Getting out of school?” I nodded three times. My Dad scooped ice cream into four paper cups, no choices, only one flavor, Frozen Pudding. We licked all the way home. Night fell.

I knew Chinatown had its own color. Brown fried rice, brown celery stuffed egg rolls, and tan ice cream, for white folks. We never ate white folks’ Chinese food. American style Chinese food boggled my mind. I liked my ice cream smooth, sweet, creamy on the tongue, no lumps reminding me of frozen udders. Frozen Pudding is white folks ice cream. It’s not a flavor I would’ve chosen. Jimmy, at the Syrian corner store, asked, “Chocolate, Vanilla, or Strawberry?” Never “Frozen Pudding?” And he put the scoops in cones, never in paper cups. With Frozen Pudding, the ecstasy at the tip of my tongue gliding along sweet creaminess, came upon jarring bitter alcohol, then bumped into a cloyingly sweet lump, raisins. Yet the ice cream tasted ambrosial.

I’d seen that word in my Greek Myths. I’d looked it up. Ambrosial meant “exceptionally pleasing to taste or smell, especially delicious or fragrant, worthy of the gods; divine.” Chinatown people worshipped many gods, each one special, with special powers. On walls, red scrolls, and figurines, the divine, a constant presence in every Chinatown home. A secret back door meeting in a foggy dark alley, free ice cream from a cheery dad, shining in his maitre d’ suit, speaking English, surrounded by men in white, eyes fixed on me, twinkling with adoration, that’s a special ambrosia that couldn’t be beat.

Since I quit Chinese School, I guess there’s no dropping by for free ice cream. It wouldn’t seem right. Ah-Gung, Ah-Bak, and Ah-Sook would still think I’d suffered through three hours of boring Chinese. It wouldn’t feel honest.

I walked on home, ice cream all gone.

At home, MaMa had food rules:

No canned food, except Campbell’s chicken noodle soup, and only with an egg dropped into the broth.

No pre-cooked packaged foods, like TV dinners.

No sodas, except ginger ale, and maybe root beer, on birthdays.

Only fresh grown vegetables and fresh killed meats, that she then cooked with pungent shrimp paste and bean sauces, fermented for a hundred years. She probably never knew about the Frozen Pudding ice cream.

Once, my dear Dad brought home a fresh duck, live and quacking. So fresh it walked on two webbed feet. It turned its head left and right, raised its wings, like I spread arms, glided down our long staircase, swooped to the front door and whooshed out onto the sidewalk. It flapped its wings but flew nowhere. This duck did not fly. It did not even quack. It waddled in our tiny kitchen. Sad eyes stared at me. I, and every Chinatown child, knew a duck in the house is never a pet.

This duck had no name. No one even called it, “Ducky.” I didn’t either, because then I might have started loving it, and there’s no sense loving someone you have to eat. A Flappy or Josephine I’d find hard to swallow. I’d be eating a friend.

“We’re not eating that duck, are we?”

“Of course, we are,” Dad said.

“We can’t eat that duck! That’s disgusting! How can you kill it?”

To eat this duck meant murder. “We are not eating that duck,” I said. “I’m not eating it. That’s really disgusting!”

“You eat chicken,” Dad said.

“I know.”

This duck had no name and no rank. I had lots of names and ranks.

“Ah–Hing!” MaMa and Aunty Cheong Sim, called. “Ah-Hing, grate the fa sang, for the fa sang tee.” I loved rice cakes. I rolled the ginger ale bottle back and forth over the peanuts, pulverizing them. “Ah-Hing, clean out the yin woh.” I dipped my fingers into watery softness and picked the fine feathers out of the swallow baby food. “Ah Hing, clean the ho see soaking in the bowl.” I ripped out the gills, removed the stone, and rinsed the rehydrated oysters.

“Ah Hing, fai loy hek, come and eat.”

“Cynthia,” Miss West called, “come up to the blackboard. Show 442 divided by 5.” I dragged my feet to the board while everyone watched. The figures blurred.

Dad phoned every night from the restaurant. “Cynthia, did you have a good day? Did you finish your homework? What did you have for dinner?”

“Yes, Yes, eggs and tomatoes.”

Neighbors and my two paper brothers’ wives, elegant brides from Hong Kong, called me by a high ranking title, “Ah-Goo,” Aunty, showing respect for my having older parents. “Hing Goo Doy, hui ni ya, Little Aunty Hing, where are you going?” They greeted me, soft and kind. I was pedaling my tricycle up the street.

On Chinese holidays and birthdays, MaMa sent me out to buy a “six pound poo-let” from the Chinatown poultry store, before I knew that a “pullet” was a little girl chicken, less than a year old, that had never had the chance to lay eggs. They yanked it right out of her cage by the neck, brought it into the back room, and I heard a zzz zzz splashing zapping sound. The chicken man handed me a brown paper bag, the pullet stuffed inside, showered and cozy. I hugged its still-warm body. On a cold winter day, it warmed me all the way home. “Ah-Hing! Mai jek gai fan loy le mo,” Aunty Cheong Sim greeted me and my pullet. I handed the bag to MaMa and Aunty Cheong Sim. Big smiles from MaMa and Aunty. The pullet never had a name either. At dinnertime, they sauced and steamed it whole, anonymous in an aluminum pan. Aunty Cheong Sim chopped it into bite size pieces and put it back together, a reassembled bird puzzle on a porcelain platter. She placed it on the dining table.

As soon as the grown ups lifted their chopsticks, and said, “Hola. Heck fan le,” we charged into the platters. My little cousin Albert’s, and my eyes targeted the tiny heart, aimed the tip of our chopsticks directly for it. Our chopsticks tangled. Neither of us would let go. His father, Uncle Cheong Sook, said, “Give the chicken heart to Didi, Elder Sister. She is older than you.” Albert withdrew his chopsticks. I grasped the heart, plunked it in my mouth, and smiled at him. I chewed it slowly, with pleasure. His father gave him the gizzard.

We were not barbaric. We had our own etiquette. Being polite meant only taking the piece facing you, not spreading your chopsticks wide, not taking a flying kung fu leap for the most delectable piece. Albert opened his chopsticks wide once, and catapulted over to the drumstick in front of his mother, my Aunty Cheong Sim. His Dad compressed his two chopsticks into one, held it in a closed fist, a weapon that came flying down, whacking his son on the wrist.

“Gup do gee ge mon tin. Only take the piece in front of you.”

Albert frowned at the chicken butt facing him. Lucky for him, Aunty gave the tail to my Llum Bak, Third Eldest Uncle, soft, fatty tail, perfect for gumming with few teeth. Finished trying for the object of his desire, my little cousin gnawed on a mushroom.

Then his face lit up. His father had placed the drumstick on his bowl of rice. While we had to learn to wait and not be greedy, generosity prevailed. “Jung yi gai-bee mo? Heck gai bee le. You like drumsticks? There, a drumstick for you,” Third Eldest Uncle said, smiling. The grownups chattered about each dish, what combination of sauces to use, how garlic, ginger, anise, citrus peel, and scallions bring out the best flavors of meat, masking the scent of an animal once alive. They chatted about how to braise tough cuts of meat to make them tender, how to heal and balance our bodies with herbs, different meats, and vegetables.

“Albert, you think other children, American children, grow up like us? Listening to food medicine talk at every meal?” I said. Albert and I loved food. I asked my Uncle Cheong Sook why Albert didn’t have to go to Chinese School. “He would learn bad things, turn into a juvenile delinquent,” he had said. I wondered why my Dad had signed me up.

I’d eaten roast duck foh opp from the grocery shop at the See Sun Company, fatty, crispy, delicious. This duck was different. This duck walking around my kitchen, looked me in the eye. How could we eat someone who looked me in the eye? When these sad eyes looked into my eyes, fatty, crispy, delicious did not come to mind.

“Americans don’t kill ducks in their kitchens and eat them,” I said. Not that I had seen many white folks. But nobody had killed a duck for dinner on Leave It to Beaver. Mr. Cleaver wore a suit and Mrs. Cleaver wore pressed dresses. They sat nice, ate nice, and said, “Pass the butter, please.” We didn’t have the Cleavers’ manners. We never had butter and we never passed food round. We had so many dishes, it would take all day. Any ways, it’s rude to pass hot platters. Lobster sauce and steamed fish might spill.

Poor duck,”I said. “I’m not eating that duck, Dad.”

The duck had been waddling around for over two hours.

“Americans are hypocrites,” he said.

“What do you mean?” I said. “I’m American.”

“What do you think about that drumstick and chicken wing you like, and that chicken liver? Americans eat chicken. They think chicken came that way, no feathers, clean, chopped, sliced. Hypocrites. They think the chicken was never alive.”

MaMa held the flapping duck by the neck and slit its throat over the kitchen sink. The blood slowly dripped into the drain. She slowly plucked each feather off, and washed the bird. I stared at the naked white body that lay in the aluminum pie pan. MaMa mixed bean sauces with mashed garlic, and rubbed it all over the bird. She stuck a scallion in the bird’s hole at the bottom, and curled its long neck around. Elegant and regal, like a swan sleeping on a silver Frog Pond. MaMa slid the duck pan onto a rack over steaming hot water in a wok. It would cook for a while. No sense hanging out in the kitchen. I wasn’t hungry. I walked into the living room, singing.

“Da-vee! Daa-vy Crockett, King of the wild frontier

Born on a mountain top in Tennessee.

Greenest state in the land of the free.

Raised in the woods so he knew every tree.

Kilt him a be’are when he was only three.”

I liked Davy Crockett’s hat, the raccoon tail hanging down the back. I turned on the television, flicked through the channels. No more “Annie Oakley,” “Gun-Smoke” came on. “Bang! Bang! You’re dead!” I flicked again. Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, wearing cowboy hats, singing,

“Happy trails to you, until we meet again.”

I sang along. I liked that they always smiled, even in an avalanche.

The Lone Ranger came on, riding his horse, yelling, “Hi-yo, Silver!” wearing a black mask that covered only his eyes. Silver reared up, when the Lone Ranger said that, without knocking the masked man to the ground. The Lone Ranger whistled whenever he needed to make a fast getaway, and Silver came to the rescue, every single time. I tried to whistle like the masked man, but only hissed. The Lone Ranger didn’t have a name. His sidekick, Tonto, called him Kemosabe. I made a serious face and lowered my chin. “Kemosabe Kemosabe,” I said in a low voice, just like Tonto.

Then,“Superman” came on. I loved Superman. He wore a red cape and flew to save lives anywhere, anytime. I grabbed a pink bath towel from the bathroom, tied the corners around my neck. I stretched out my arms, marched around the living room, chanting,

“Faster than a speeding bullet.

More powerful than a locomotive,

Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound,

Look, up in the sky!

It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Superman!…

Superman fights a never-ending battle for truth, justice, and the American way.”

Superman had not just one, but two names, two disguises. Superman switched into a suit and glasses, and became Clark Kent, the “mild-mannered reporter.” I loved that he had two identities, one secret, with super powers.

“Hek-fan le! Time to eat rice!” MaMa called.

I flicked off the TV, untied the towel, ran into the kitchen. MaMa lifted the bird out, golden, fragrant. Sitting at the red formica kitchen table with MaMa and Dad, I looked at the glistening skin. It didn’t look like a duck anymore, at least, not the kind that flew south for the winter in triangle formation, honking. My beautiful duck had a name now. It had turned into “Chui Opp.”

Dad chopped it into pieces easy to pick up with a chopstick. He dropped a duck leg on my bowl of rice.

I bit into it. Fragrant, Fatty, I thought, Delicious.

“See?” Dad said, “Tastes good, right?”

“Yes, it tastes good.”

What’s to become of me, a duck-loving girl enjoying the fresh kill?

I couldn’t imagine my teacher, Miss West, slitting a duck’s throat and cooking the dead duck for her school lunchbox. She heated up cans of thick yellow goop, Campbell’s corn chowder, on the school radiator, and made us do excruciating long division problems afterwards.

The next day, I laced on my sturdy gray Oxfords. MaMa said, It’s time to go downtown, to Jon Mah Sa, Jordan Marsh, to buy a zipper.” I had to accompany her. That’s what you do when you’re born to a MaMa who can’t speak with most of the world. MaMa and I walked up Washington Street, past the topless bars, doors shut, windows dark, except for the blinking neon at The Naked Eye.

I lived in two worlds, a Chinatown world and a Downtown world. Here was this third world of naked black and white people. MaMa tried to explain it to me once in a while. I walked next to MaMa. I glanced at a poster of half naked men and women, and past a woman looking bored, dressed up and standing by the street. Another in a pink feathery shawl spoke with a manly voice that switched into a high pitch. A woman in a shiny silver sequin top, tight black leather shorts, and tall white cowboy boots, blinked her black, glittery eyelashes. She stood next to a tall black man in a cowboy hat, flashing big, shiny stones on his fingers. He snapped his fingers and pointed. The women scurried, moving to where he pointed. A white car pulled up and the cowboy hat bent down, whispering into the rolled down window, talking to an old white man, who handed him rolled up bills. We walked on.

I smelled old beer mixed with urine. My gray Oxfords caught on the sticky sidewalk. An unshaven man leaned against a building, eyes glazed. He stumbled straight towards me. I moved closer to MaMa. She said, “You don’t have to be afraid of the duey mow. They drink too much whiskey. They don’t know what they’re doing. They can’t control themselves.” We walked by the 10 Cents Hot Dog stand, crowded with customers. I moved to MaMa’s other side, close to her, matching her stride. The shirtless man on a poster, leaned over a woman reclining, her low cut white blouse, falling off her shoulders, head thrown back, throat turned up. Her face grimaced, looking pained. We walked on.

We passed the Red Cross Shoe Store where MaMa had insisted on the gray Oxfords. I had liked black patent leather Mary Janes, party shoes with raised heels. MaMa said, “Those shoes are cardboard shoes, they’ll ruin your feet. You must wear good shoes to have good feet.” “These shoes are old lady shoes,” I said. I stomped and whined. It didn’t work. MaMa dressed me in the gray Oxford shoes, red and navy plaid pleated skirts, navy knee socks, and a camel’s hair wool coat with a double row of buttons down the front, and a belt running across the back. I was a British school girl reciting Chinese in Boston Chinatown. We crossed the street. In the store window stood stiff, white mannequins, posing in fur coats. We opened the door and entered Jordan Marsh’s bakery section.

The bakery ladies wore aprons, and bustled about, filling boxes. They’d stacked high piles of colorful imported cookie tins. We looked in the bakery cases, at peach and strawberry tarts, blueberry muffins that MaMa called poo pi doo kik, raisin cakes, and MaMa’s favorite, whipped cream puffs. She called them, kee leem kik.

“Let’s return and buy later,” MaMa said. We rode up the escalator, and approached the counter that said, “NOTIONS.”

“My mother wants a gray zipper.”

The girl brought out a tray of zippers, all colors.

“How mu-chee?” MaMa said. Not that she’d understand the answer.

“One dollar,” said the girl.

“Yit moon,” I repeated.

“Ask her if she’d sell it for fifty cents.” MaMa smiled her sweetest smile, the one she reserved for white folks.

“MaMa, she doesn’t own the store. She can’t sell it for fifty cents. She just works here.”

“Moon a kui ya. Doi moon a kui ya. Ask her. Ask her again.” Ma Ma smiled that smile again.

MaMa grew up in the market stalls of San Ba, China. Her father sold needles and threads, and buttons, but definitely not zippers. They bargained all day. She helped her father mind his stall. By the time she had turned eight, MaMa knew a good price and how to talk up the ladies who went low. Rules had reversed in America. Here poor people were fat and rich people, thin as starving goats. And zipper sellers didn’t own any zippers.

“My mother wants to know if you’d sell it for fifty cents.”

“Oh no, I’d like to, but I’m sorry, I can’t.” She smiled. I was grateful that she smiled.

“Kui wah mm duk. See, MaMa? I told you. She says she can’t.”

MaMa handed over the dollar and took the zipper. We bought two cream puffs and two blueberry muffins on the way out. We walked home, past the streetwalkers and dancers hanging out before work, about to go topless. On this day wires zapped and crossed, mixing up my two worlds. We climbed our apartment stairs, home with our pricey zipper. MaMa stitched it onto the dress she was making. I licked my kee leem kik. When wires had crossed, Chinese and American schools were not much help to me. I was on my own.

Chinese and American School issued report cards each term. In American school, I got A’s, with a plus or a minus here and there. Chinese School ranked me. It seemed sweet girls were #1, #2, #3, and even #4,#5, obedient girls who looked down at their shoes whenever they talked to the teacher. My Chinese school friend, Mary, always #4 or #5, taught me a trick. If the old men in Chinatown streets stared at our swelling bodies, she said, “Stare at their shoes.” I stopped. I stared at the men’s shoes, unflinching. The men looked away, stared down at their own shoes, as if checking for pigeon poop. It worked. They looked away. I thought Smart Mary deserved #2 or #3. Last year I had managed a rank of #8. That surprised me. Most terms, I ranked #10, not bad in a class of forty boys and girls. It had to do with test grades. I felt #10 was fine. I accepted that I’m a 10 in Chinese. In American School, I earned all A’s and sat in the first row, first seat, which Miss West said was “the seat for the smartest boy or girl.” Miss West had made it a seat of honor and I had believed her.

Then I caught on. It had to do with my wearing glasses. Everyday, she reminded me to wear my pink glasses, which I forgot often. It was hit or miss. MaMa never reminded me to wear glasses. She believed little kids did not really need glasses.“Only in America,” she said. She thought glasses ruined kids’ eyes. Only Miss West ever told me to wear glasses. I didn’t see what the big deal was. There wasn’t much to read in school or at home. The numbers in Long Division on the blackboard, those I found a mystery. Long Division was, honestly, just too long. Adding straight columns, carrying numbers over, more to my liking. With Long Division, the columns zigzagged. One slip-up, and the answer got lost in a maze.

The idea of me attending Chinese School started two and a half years earlier at supper. My Dad had said, “It would be good for you to learn to read and write some Chinese. I signed you up. You start Monday.” He didn’t ask me. He notified me. I wasn’t sure if that meant I had to stay.

The first lesson of Book One went like this:

| Hui hui hui“ | Go Go Go |

| Seng hok hui | Go to school |

| Ngoy hui, ni hui | I go. You go. |

| Ai-ga yit tai hui | Everyone go to school. Together. |

| Loy loy loy | Come Come Come |

| Loy ook si | Come read books |

| Ni loy, ngoi loy | You come. I come. |

| Ai ga yit tai loy. | Everybody come read. |

Simple to understand. But what was the point? So far, the book seemed silly.

Then, the text got interesting. A boy named, LLiu-Ma-Gong, took a rock and smashed a ceramic water storage vat. I had never seen one, but the black and white drawing looked pretty.

| Na sek how | Grabbed a rock |

| Ah po gong. | Smashed the water vat |

| Gong sui yit tai fong | All the water flowed out at once. |

I memorized that rhyme on my own. I don’t think LLiu Ma Gong ever got punished. It must be a famous old legend. MaMa even knew it. She recited it to me one day, a lot of effort for my MaMa, a poor village girl from a big family, who only went up to Third Grade. Then I read further a bit.

| LLiu Ma-Gong | Siu Ma-Gong |

| Tong ming | Intelligent |

| Yu ahm leng | Brave |

Intelligent. Brave.

Maybe he had saved somebody from drowning. Maybe some situations called for breaking even precious things. I read on.

| Gui lel pang yu meng | Saved a friend’s life |

| Oo deh, Lliu Ma Gong. | Thank you, Siu Ma Gong |

He saved a friend who fell in the water vat. They never said that poor child’s name. Anyway I was more interested in the savior than the poor kid who fell in. I liked heroes.

Chinese School had sometimes been fun. I slipped potato chips and M&Ms out of my desk and munched them with a straight face, when the teacher turned his back. I chewed without crunching. I had pre-copied the Chinese text for the “Write-from Memory Test,” slipped it out of my desk, and passed it into jolly Big Mr. Wong. He smiled. I smiled back. I stood in front of Mr. Leong one day, reciting text aloud for the “Recite from Memory Test.” Halfway through, he turned to talk to someone, and I announced, “I finished!“ Mr. Leong gave me an A. He liked girls. We knew to run fast so he couldn’t grab our legs. I cheated smooth as ji ma wu sweet black sesame soup.

Another day, ancient Mr. Yee, rimless glasses and receding hairline, walking up and down the aisle swinging his stick, stopped at my desk, and for no reason at all, said, “Put your hand out!” I placed my hand on my desk. “Palm up!” he said. I turned my hand over. He raised the rattan, ready to slam it down hard. Just a second before it hit, I withdrew my hand. He hit the desk. “What’s your family name?” he said.

“YEE,” I said, looking him in the eye. I thought he would ask for my hand again, but he walked away, shaking his head, mumbling,

“YEEs are just like that.”

I had shamed my entire clan? Why did he say that? He’s a YEE. He must be a fake YEE, a paper YEE, I thought. To me, it seemed natural, smart, to move quickly away from a stick that was about to hurt me.

After two and half years, I could read and write some. I memorized and recited Chinese texts aloud, nem si, they called it. I could write passages from memory, mak-si. I never had to explain what the text meant. In between tests, I indulged in carnal pleasures, salty potato chips, creamy sweet Twinkies, and salty sour plums. I stayed until the middle of Third Grade. Then I felt I had learned all I needed to know.

A few days before I quit, we had gotten report cards in Chinese School. The subjects were written in Chinese so I couldn’t read them all, but I could see the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s, all in a neat row. Then I saw it: 60, in bright Red Ink, for “Gung Ming, Civics.” Gung Ming, a thin black and white book with a tan cover, taught by Short Little Mr. Wong, black square glasses on a stern face that never smiled, roaming up and down the aisle, waving a rattan. The Red 60 had pulled my rank down to #11.

I had a limit. The lowest I’ll go is #10. Didn’t they know my Dad loved me #1, 100%, all the time? The Chinatown merchants had started the Chinese School to make American borns more Chinese. The volunteer teachers, grocers, not real teachers, had insulted me. I got ripping mad. So I’d quit. I turned off my Chinese brain. I stopped paying attention. I decided never ever to return.My parents were busy. I wouldn’t bother them with my problems. I didn’t tell them I quit but quitting and not telling them weighed on my mind.

Things are seldom as they seem. I spoke Taishanese, a country dialect from southern China, like a Chinese peasant girl. But I wasn’t. I was a city street urchin from Boston, United States of America. Don’t let my face mislead you. A Boston accent crept into my English, and into my Taishanese, too. I spoke Chinese with a Boston accent. I spoke a country dialect from the Pearl River Delta of Guangdong, China and also the Boston English I had learned in American School. I knew words like pollination and purgatory. When I stumbled in baby Chinese, the grown ups in my family called me, “Bon Hoong Siu, Half a Bucket Full.” “Half a Bucket Full” meant I could pass, well enough. Chinese School tried to make me a Full Bucket Full, but it didn’t work. They did not teach us to talk, only to memorize, read, and write. When I tried to ask a complex question in Chinese, my tongue twisted, like trying to explain to MaMa what my life was about, but only knowing food words.There’s only so much a girl can say about salted fish juice on white rice.

I needed to talk to MaMa for some things. I said, “Ngoy hui ak ma? Ngoy lleng hoong ne sis-see-dah hui cam. Ni o koy teem ge meng. Can I go?” “I want to go to camp with the sisters. Sign here on the line.” I checked her scrawly signature to make sure it was passable. I needed her written permission so I could go to a Girl Scout Day Camp by the Charles River, with the nuns. I pronounced the word,“camp,” dropping the “p, ”and added a Chinese accent, so it came out as, “hui cam.” No “p” sound, the way MaMa said it. MaMa understood it meant I would be gone most of the day for the summer, safe with the nuns. That was good enough for her.

On top of Half a Bucket Full, they called me, a “Hollow Bamboo,” a “Jook Sing,” hollow all the way through, from end to end. Chinese going in one end and leaking out the American end, their opinion of American borns. In return, we called the China born, “Bamboo Nodes, Jook Kuk,” bamboo knots, nothing flowed. Smarts entering through one entrance, then stuck.

I awoke every morning to two worlds, each mysterious to the other, slowly growing into understanding both. Until I grew up, I accepted, as an integral part of my life, that I felt embarrassed, mortified even, whenever I ventured beyond Chinatown with MaMa. Chicken noodle soup with a dropped egg for breakfast on cold winter mornings, sliced ham on Wonder Bread for school lunch, and salted fish pork cake, my favorite, steamed with lots of ginger over rice for dinner. I learned never to eat a ham sandwich on white Wonder Bread for dinner, as MaMa would scold me for junk snacking. And definitely, no fragrant, smelly salted fish over rice for school lunch. I tried not to mix my two systems.

Sometimes signals got crossed up, no matter how hard I tried. That’s another thing that happens when your MaMa didn’t understand the world as you did. Sometimes my wires tangled, and I did the American thing in a Chinese setting, and the Chinese thing in an American one. That made for problems. But my Chinese folks always laughed it off. ”What can you expect from a Jook Sing, a Hollow Bamboo?” They chuckled when they said that, as though proud to have a Hollow Bamboo in the family. Some days, the nickname offended me. Other days, I felt freed by my family’s low expectations. “I am a Jook Sing, so I don’t know that,” I’d say. Life at the intersection of cultures gave me options. A Hollow Bamboo, who is also a Half-a-Bucket-Full kinda girl, a Bon Hoong Siu, Jook Sing Niu, doesn’t need Chinese School.

My neighborhood friends, schoolmates, and I were the new generation in Chinatown Boston, born post-WWII. We enjoyed great freedom. We shared a secret code: English. Co-conspirators, running circles around our immigrant parents. But not around my Dad, who was fluent in Chinese and English, an important detail I sometimes forgot. Whatever we didn’t want our moms to know, we said in English. They called us,”Ngow Jook Sing,” with a smile. We were their beloved “Crazy Hollow Bamboos.” The words, Hollow Bamboo, always preceded by “ngow,” meaning, “crazy,” always said with a smile, so we knew it didn’t quite mean “crazy,” as, “not in ones’ right mind.” It meant “crazy” as in, “wild, following no rules,” free, like wild horses. How could we ever stay mad at our mothers, who were proud of their ignorant children? They said we had intestines that didn’t twist and curve in our bellies, but uncoiled in one straight tube to our big toes. “Em cheng em oo; yit hel cheng lok hui gek ji gung.” I closed my eyes, trying to imagine my food going directly down to my big toe. That meant, we didn’t know how to twist and turn, how to avoid danger. They thought us guileless, overly trusting, foolish.

I grew up without strict rules, no bedtime, no curfews, no weekly allowances . “Go to bed when you’re sleepy.” “Come home in time for dinner.” Only MaMa never set a special time for dinner, so I went by the sun’s light. “If you need money, take what you need from the coffee can.” My parents trusted me to decide, work out my own conclusions, find my own way. MaMa said, “Don’t look at the girls working in the alley.” I stared anyhow. I cheated in Chinese School though the grocer teachers were friends of my parents. MaMa often wanted my Dad to have one on one talks with me, to explain why I should choose to do something wiser, kinder than what I was doing. “Is it wise to stay up watching TV when you have school tomorrow?“ I watched until after 10:00 pm. The next day, I was too tired to play and not happy. After that, I made myself go to bed before 9:00. I had lots of practice choosing.

Once, on his one day a week off, Dad started the talk at dinner. “Why did you stay out playing so late?” I didn’t answer. I felt tears rolling down my face, my nose filling. I couldn’t eat.I didn’t feel I had done anything wrong, but he was my Dad. I loved him. I had disappointed him. MaMa said, “Don’t teach her while she’s eating. Talk later. She can’t eat rice when you talk that way to her.” To MaMa, eating rice was serious, more important than obedience.

I walked in circles until after the sun set. I didn’t want to talk about Chinese School, not one on one, or two to one, or four to one. It wasn’t that important. Quitting should have been no big deal. A few stars glittered, the half moon shone. Almost time to head home. I looked down the street towards Kneeland. I saw my Dad and my Uncle Cheong-Sook running frantically towards me. The Posse. Just as I had seen on television.

Two Chinese men in dark suits galloped down Hudson Street. I stood on the corner of Hudson and Oak, when I should have been reciting, “Go go go, go to school.” I was killing time in the empty lot, a nine year old renegade mustang runaway walking in circles, flipping pebbles. I’d soon be roped, hog-tied, corralled for sure. But they rushed on past me, without a glance.

I watched my Dad and Uncle’s rears, as they galloped on down the street. My Dad and my Uncle Cheong Sook, rushed towards our home way before quitting time. They hadn’t noticed me following behind them. They looked disturbed. We arrived at my house, heard sounds from the top of the stairs, from my home, from our second floor apartment.

“Open the door!” someone shouted.

“F.B.I.!”

“Open the door! You hear?”

“Open this door!”

Fists hit wood.

Bang! Bang!

Palms slapped wood.

Bang! Bang!

A man’s voice.

Shouting.

Shouting English.

A White Man’s voice, a Lo Fan.

“Open this door! Hear me?”

More shouting.

More banging.

MaMa and Aunty Cheong Sim had called my Dad at the restaurant. At the top of the stairs, the two white men paced on the landing.

My Dad asked, “Who are you?” “What are you doing?”

MaMa and Aunty Cheong Sim unlatched the chain, opened the door a crack, and looked out.

One White Man, flashing a card, said, “F. B. I. Federal Bureau of Investigation. I showed them my badge.”

“How do they know what your badge means? They don’t know English. You scared them!” Dad looked angry. “Why are you scaring women? Why?”

“We showed them our badges,” the other White Man repeated, face turning red.

“They don’t know what your badges say! They don’t know what your badge means!” Dad looked somewhat angry, but he hadn’t turned red. Uncle’s brow wrinkled with worry.

They made a small circle in front of our apartment door. I stood behind them.

“Your badge means nothing to them!”

The White Men looked at each other, shrugged their shoulders. They whispered to each other. Then they rushed back down the stairs and drove away.

Dad looked at me. “Why aren’t you in Chinese School?”

“I quit,” I said.

“Oh,” he said.

And that was the end of that.

Chinese School wasn’t that important. Saving family from loud, red in the face, screaming White Men, was way more important than Chinese School.

Still, the next day, two other White Men came, not in the dark of night, but in bright morning. They went into the apartment beneath ours, Grandma Wong’s. I looked down from the top of the stairs. I tiptoed down and peeked inside. Grandma Wong always made steamed rice cakes for me in her cozy basement kitchen and asked about my day. I loved chatting with her. I loved how she shuffled along, her hands by her sides, wrists bent, fingers pointing out, a penguin. I copied her at home, just to see how it felt to be a penguin, but never in front of her. That would be unkind. The men were tall, white, and wore dark suits. They had never tasted her rice cakes, nor did they know she was a beautiful, kind penguin. They saw a silent, timid creature without a name, without rank. The kind of creature one can roast and eat.

Grandma Wong, bent and shrunken, stood by her son. He sat at the kitchen table and spoke with the taller white man, then told Grandma what the man had said. I watched. The two men asked a lot of questions in English, while Grandma Wong’s eyes darted left and right. I couldn’t hear what the men said. They looked serious. She looked nervous, confused, but her mouth smiled, polite. I watched the two men get up and walk out the door. I watched the men’s rears swaying, bandits swaggering, farther and farther away from us. They slipped into a black car. It drove away.

Dad spoke English and chased bad men away, snarling F.B.I agents, like he rolled the white drunk who was once breaking into our apartment. Flying super hero, galloping white-hatted cowboy, my fearless, wise, and kind Dad, I loved him. Dad forgave my transgressions, pretended not to know the English alphabet when I spelled out secrets to my little cousin. He spoke to me in a soft voice. “Always do what’s kind.” Dad had rescued MaMa, Aunty Cheong-Sim, and Grandma Wong from angry white men. The boy in my Chinese book smashing a porcelain vat with a rock, spilling precious water everywhere, was a hero. Dad chased away men who wore important badges, men who scared women unsure of the rules, women who could not speak to anyone outside of Chinatown.

I climbed back up the stairs to my second floor apartment. I had borrowed a book from the Tyler Street Library. I thought I had lost it. Dad had paid a nickel fine. I felt bad about Dad paying for my mistake. A week later, I found the book underneath the sofa cushions. I owned my very first English book. The cover showed a white picket fence with an opened gate, and entering it, a little blonde girl with ringlets. She did not look like me. Across the top, the title read, Open the Gate. I turned the first page and read. I overheard MaMa asking Dad why those Lo Fan White Men, came. He said they were looking for breathing poison, white powder, but came to the wrong house.

That night, laying in bed, I wondered if a duck thinks in duck language. What does it think as the knife comes close? Does it dream of Duck heroes? Does it cry sometimes? What would happen if white men with badges and guns came back, and brought more white men, more guns? What would happen to me if they took Dad away, killed him? Did a Daddy penguin talk to his newly hatched babies about how to jump on ice floes? Did he protect them from whales, sharks, and seals? I closed my eyes and drifted off.

The next morning, I grabbed my pink glasses and walked to school with my friend, May. We passed the vacant lot where a girl had paced in circles killing time. I walked into class, and sat in my seat, first row, first seat, waiting for Miss West to say, “Cynthia, where are your glasses?” I had a plan. I would whip them out, put them on, surprise her with my glasses and magnificent grasp of long division, and the columns wouldn’t zigzag out of control. Divide and divide down, keep all the columns straight, and end with no remainder, evenly divided, up on top. I would master Long Division with my pink glasses. She would say, “That’s my smart Cynthia. That’s why you get to sit in the first row, first seat. It’s the seat for the smartest child in the class.” I would play along, smile, and hope she is right, because after school, I’m going out to play.

I met Susan at home. She lived above me. She had ranked #1 in Chinese School in an earlier class, but she had quit during First Grade. She was amazed I had stayed so long. Her mom had told her to give it a try, so she had, and hadn’t liked it at all, so she was allowed to quit. Susan spoke English with a southern accent. She said, “pin cel” instead of “pen cel,” because she’d lived in Arkansas. We grabbed our hula hoops and ran out onto the sunny sidewalk. I put my red hoop around my waist and she, her pink one. We started the hoops with our hands, balancing them on our hips, then let go. The hoops slipped down, and we twirled the hoops, faster and faster, propelled by the gyrations of our hips. We challenged gravity. We controlled speed. We twirled faster.

“All right, you Chipmunks!

Ready to sing your song?

I’ll say we are!

Yeah! Let’s sing it now!

Okay, Susan?

Okay!

Okay, Cynthia?

Okay!

Want a plane that loops the loop.

I still want a hula hoop,

We can hardly stand the wait

Please Christmas, don’t be late.”

We sang in unison, again and again, voices spiraling up and out into the air. A V of ducks flew over us, heading south for the winter, just as Miss West had told us they would. If Ducky and Josephine’s friends and family were glancing down, they’d see a circle of red, a circle of pink, twirling and twirling, and in the center, two black dots, two little school girls, freed, hips flying, propelling their energies up and out, their voices mingling with the honking of the ducks, flying wild and free.

What I remember most about my MaMa was her back, her slender back. Bent over fabric, fabric slithering through her thin fingers and tiny bent palms. Needle snapping up and down, puncturing fabric. Her silk slippered feet, side by side on the pedal, pressing hard, pressing light. Fabric moving fast, fabric moving slow. Machine plugged into magic current. Electricity in old thin walls. I, watching. She, chatting all the while, about eggnog and chocolate milk, about white teachers and washing hands, about drunken men and not to fear, about money and courage, rice and strength, life and death. She never lifted her head and looked back at me, never walked over to me, never lifted her hands and caressed me. Only her voice, the sound of the machine. Her bent back soothes my childish heart.

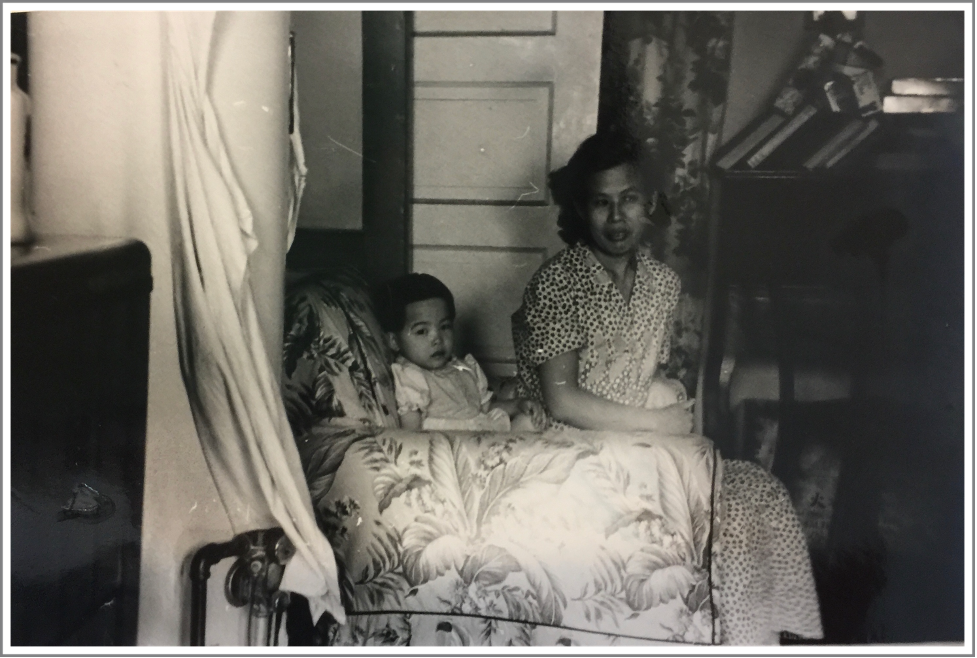

When I was a baby, she’d hoisted me up on her back, bundled me in her silk embroidered bai, tied me close to her, four cords crisscrossing her breasts, a knot against her heart. She’d leaned my face in, my arms hugging her warm arms, I slept. Her hands free, she worked and worked.

我记忆最深的是我妈妈的身背,她那纤细的身背,弯曲在布料上。布料滑过她瘦弱 的⼿指和⼩⼿掌,针上下穿刺着布料。她柔滑的双脚,并排在踏板上,阵重阵轻。布料移 动着,时快时慢。衣车电插插入了如有魔法的电流,电线就在那旧薄的墙壁⾥。我,看着 她,在说着蛋鸡和巧克⼒⽜奶,说⽩⼈⽼师和洗⼿,说喝醉的男⼈不要害怕,说⾦钱和勇 ⽓,⽶饭和⼒量,⽣死。她从不抬起头看着我, 从不抬起脚⾛到我身前, 从不抬起双⼿ 抚摸我。只有她的声⾳,机器的声⾳,和她弯着的身背抚慰了我幼少的⼼灵。

曾在我还很⼩的时候,她把我背在背后,把我放在她的丝绸刺绣婴⼉背带⾥,把我 放到她的最近,四根绳⼦交叉在她的乳房上,⼀个结打在她的⼼上。我的脸俯着她身 体, 拥抱她温暖的背部, 我睡了。她的双⼿⾃由,努⼒地⼯作。

*******************

Chinese translation of “My MaMa’s Back” by Sarah Cheung

In the fall of 2020, “My MaMa’s Back,” was produced into a voice over/archival photo video by filmmaker, Daphne Xu, with Chinese subtitles by Sarah Cheung. It was shown at the 29 Oak Street Wall Projection Series, sponsored by the Chinatown Community Land Trust. The video was also featured under “Covid Shorts,” at the 2020 virtual Boston Asian American Film Festival (BAAFF), organized by Executive Director, Susan Chinsen, and co-sponsored by Arts Emerson.

I thank Christine Nguyen, Director of Development and Communications, and Angie Liou, Executive Director, of the Asian Community Development Corporation for their support, publishing my work on ACDC’s social media.

The Kwong Kow Chinese School was founded in 1916 for immigrants in Boston Chinatown. Located on Oxford Street in the 1950s, it moved to its permanent home in the Chinese Community Education Center at 87 Tyler Street in 2007.

“My MaMa’s Back” is a salute to the immigrant women garment workers of American Chinatowns and their children, many of whom are the educated, professional, activist leaders of today’s America.

Hi Cynthia,

Thank you so much for sharing. Love every word. I always enjoy reading your writing. You are very talented. Keep it up. Thanks again.

Therese

___thank you so much for reading my new story before it comes out Tuesday!_____________thank you always your for your support and kind words! Cynthia ______________

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love this story and I appreciate how similar immigrant experiences in Boston shaped our upbringing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for reading ! Yes I’m

proud and glad to have grown up in an immigrant enclave in Boston. It shaped our perspective and enriched us immensely ! Thank you. ❤️

LikeLike

This is wonderful writing. Thank you very much for sharing parts of your youth with me.

thank you very much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautifully written. Thank you for sharing your poignant memories with us. I have forgotten most of my Taishonese but when I read your stories aloud I hear it again and understand many of the same childhood memories. Growing up in the South End instead of Chinatown made my own life that much lonelier and finding friends in C-town in high school made me envious of kids raised there. How little did I really know of what life was like in the neighborhood. Your writing about those few blocks makes my heart remember and like the story-tellers of so many native peoples, your song makes me weep with sadness and gratitude. Stay strong dear friend!

Thank you so much for reading, dear sister ! I do feel we are sisters of a certain time and place. I attended the Holy Trinity School in the South End grades 4-8 where Castle Square housing now stands .

LikeLiked by 1 person

This a powerful story Cynthia. I can relate to all the food. I would LOVE to see all your stories published in a print book for the next generation!

Thank you Fay and Harry ! You are always such loyal passionate readers! I’d love ❤️ to publish a book but I don’t know how ! I need help!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was just about to write what Fay Lee said – I would love to see you publish your stories as a book. You can self-publish books on Amazon, both in print and Kindle format.

I’m the grand-daughter of Eastern European immigrants and love reading the stories of growing up as first or second generation children from other ethnic backgrounds.

Thank you !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Love, Love Love the story Cynthia!! It brought back such wonderful memories of our childhood. Thank you for preserving the history with your amazing storytelling. I’m sure that my grandchildren will also love reading your stories. They will be amused that their grandmother was mentioned in your story. ❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are in my story just like your brothers! You are an Integral and important part of my happy Chinatown childhood memories ! Thanks for reading it! Share with anyone you think might be interested! 👌❤️🤗🤗🥂🌷🌷

LikeLike

Dear Cynthia,

I have been looking forward to reading your new piece, and once again, you did not disappoint. I read Duck from beginning to end with anticipation of each event that took place. My excitement after the first few sentences got me to run to Albert to stop what he was doing to hear me read your story aloud to him, so that we could experience this time period together.We laughed often at the humor that you sprinkled throughout your piece. We recognized almost every one you wrote about. We loved the Toisanese you phonetically wrote in with the English translations. We recognized the people, the places, and the events. Your descriptions took us back in time and we enjoyed walking down memory lane through your writing.I read each sentence, each description marveling at each word you chose to move the reader along your growing years. I read and re-read certain sentences that were so truly and beautifully written. There is magic in your writing….and we are your captured audience just waiting for more of your stories to come out!

A devoted fan and follower,

Bonnie Y.

You’re a pretty good writer yourself . I love reading your thoughtful responses! Thanks for telling me in Florida, “next Wednesday we are taking you out to dinner and you better not say you did zero!” It took a year to write but I finished! Thank you 🙏 for always being so supportive of my writing ❤️❤️!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing your memories of growing up in Boston Chinatown . I am always amazed at how much you remember of your childhood, and are able to capture the details in your writing ( Duck).

Given that I grew up in Boston Chinatown, I can relate to many of your stories ( Chinese school and its teachers, Jordan Marsh blueberry muffins, buying live chickens/pullets from the chicken man, Mrs. West , walking quickly through Combat Zone, etc.

Thanks for the memories.

Anna M. Wong.

Thank you Anna for always been such a loyal reader and supportive too! ❤️🦆

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like Bonnie Y said..I eagerly await the next story. Your writing is vivid & brings back memories. Forwarded them to my son, your student, CL-C.

~BL-C

LikeLiked by 1 person

Even though we grew up a decade apart and on different coasts our childhood experiences are very similar from quitting chinese school to being rebels in disguise. I always thought I was the only one who didn’t live up to the ‘norm’ of chinese families.

Thanks for bringing back those memories of childhood. We roamed the streets, explored our neighborhood and beyond on our bicycles never telling parents just how far we went on those fun filled weekends. Freedom was what we had and enough smarts not to abuse it because it could’ve been taken taken away swiftly.

Anyways, enjoyed your short story about our hoisan héritage. I hope you continue to write i look forward to reading your work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much! ❤️🥰 I think we were free, independent thinkers, lucky to have the grounded safety of a tight-knit community and loving, responsible parents! Thank you for reading and I’m glad you enjoyed my story .❤️🦆🤸♂️🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much ! It’s nice to hear of our common experiences!❤️

LikeLike

Rereading your stories, just magnificent. I am not alone.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aww thank you so much! ❤️My greatest joy is to hear from our community of Chinese Americans, who really know and understand viscerally, the nuances of our Hoisan American childhoods, minus the white gaze .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Cindy. You are a fabulous writer. I felt as if I were experiencing your childhood with you. Actually, it was very reminiscent of my own growing up as a first generation American. Only my people spoke Yiddish. Hope you are doing well.

Norm Finkelstein

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much, Norm ! A famous published writer like you liking my writing is a huge huge compliment! Thank you for reading my latest story . We do have a lot in common . Jewish and Chinese cultures are so similar . I miss our daily lunch chats ! My reheated soup and your fancy bread sandwiches ! Such sweet memories !

LikeLike

Thank you so much for letting me read your book “Duck”. All the events are new to me and open my eyes to a different situation. Having grown up in “Pennsylvania Dutch” country, all your experience is history to me.

LikeLike

Thank you Jennie from

Pennsylvania Dutch Country for reading my Boston Chinatown stories!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Cynthia,

It was a pleasure to meet you at lunch today.

I just finished reading “Duck” and thoroughly enjoyed it.

Well done. It brought back fond memories of my own immigrant story.

-Manny

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you reading ! It will become a dance for the Momentum Greenway Dance Program this fall. It Beas a pleasure meeting you and Andrea today !

LikeLike